2019 was a dark year for Eskom.

Day after day, the energy provider trembled under the burden of keeping South Africa’s lights on. While the nation squinted in the darkness, technicians clocked into work with the herculean task of keeping the grid alive. Protecting the grid meant killing the demand, and there was a lot of demand to kill.

The nation’s sockets were begging for more and more, while the mismanaged power stations could only strive for less. As this got further out of hand, the company’s leadership feared a complete meltdown. A meltdown that would wipe out 95% of the country’s supply. A meltdown that would take weeks to reset and years to recover from.

Although the grid still stands today, it has never tip-toed far from this perilous edge of collapse.

This anecdote resonates across the continent. In much of Africa, one cannot just rely on the grid. Six hundred million people, mostly scattered across Sub-Saharan Africa, remain unplugged. For them, blackouts seem to be a distant, privileged problem.

What does the future hold?

The conventional playbook for grid expansion is one of big infrastructure development. These projects chase economies of scale through major, up-front investment with long return profiles that accrue over twenty or more years. To complement these hefty power stations, transmission lines fan out through successive sub-stations to people’s homes. China went through the same transition in the second half of the 20th century. Their central planning coupled with an inflow of investment multiplied the grids capacity and its reach by a few orders of magnitude.

This strategy is failing in Sub-Saharan Africa. Mismanagement and poor project governance are prime suspects for the crime of charging the world’s poorest with the highest electricity tariffs. To reduce the financial burden, corners are cut by spending even less on maintenance. Power stations crumble and the vicious circle continues. The result is that debt piles on as the government desperately hands out lifesaving subsidies and loans to the drowning utilities sector.

The outlook appears bleak, but there is an end in sight.

Technology has changed the landscape of power generation. Economies of scale do not matter as much as they once did. A personal solar panel could outperform the returns of a multi-billion dollar power station in this region. Without the need for centralised spending, the region does not have to wait for the grid to play catch-up to electrify homes.

In my previous article, I wrote about three distinct phases of electricity generation: the monolithic grid, the unbundled microgrid, and the rebundled, platform grid. Sub-Saharan Africa is poised to leapfrog the first and land into the world of personal and microgrids.

On energy unbundling, I wrote:

The most popular approach is to buy your own supply. This mostly applies to solar: procure your panel, stick it on your roof and reap the rewards. A few direct to consumer brands are popping up in this space, epitomised by Tesla's solar roof. There is a streamlined website with a stylish panel design and even an app in dark mode.

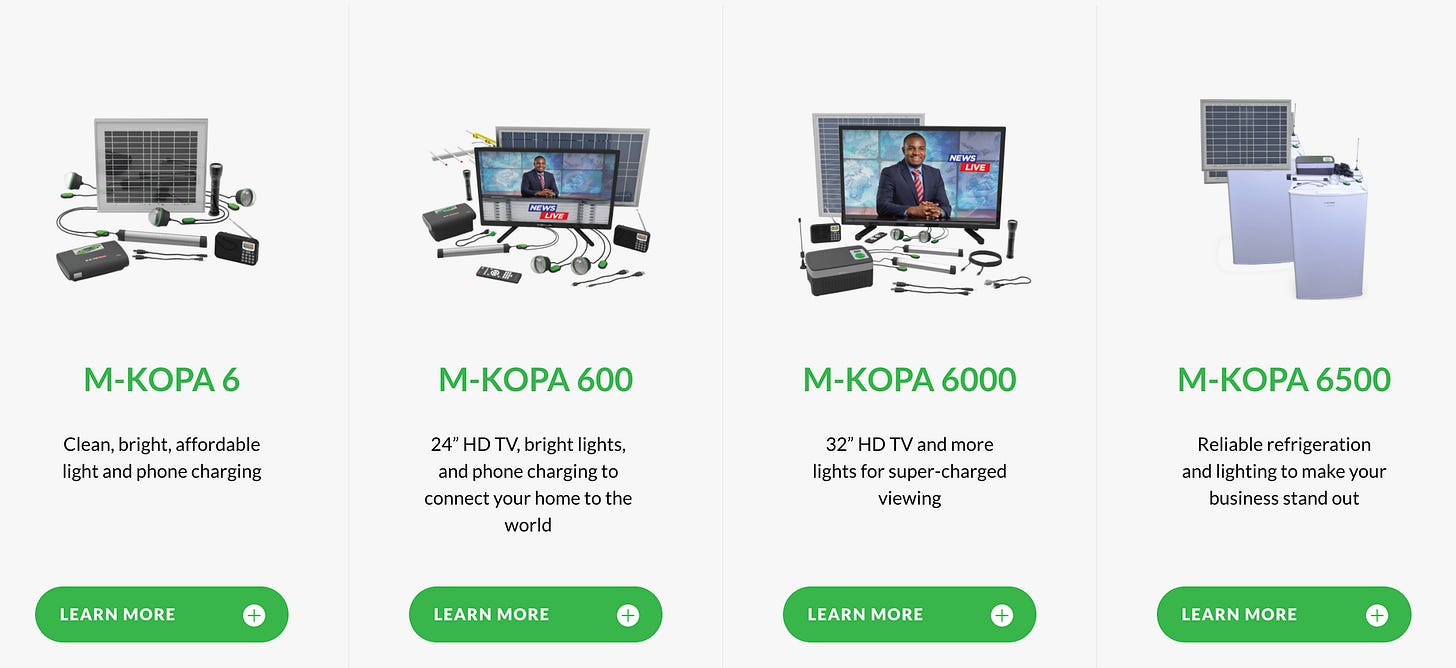

While Tesla Solar focuses on lifestyle branding, companies like M-Kopa have a very different sell. Their websites do not talk about design or even about the benefits of renewables but focus far more on the impact of access to energy.

M-Kopa is not competing with the established grid but in most cases with a household’s kerosene lamp. How do you sell electricity to someone without a light switch or a power socket? You create a new bundle.

With the purchase of a solar panel, you can expect to find a few lightbulbs, a television and even a mobile phone thrown in the mix. First time buyers are not looking for a cleaner way to produce energy, but for an opportunity to consume goods that were once inaccessible. Solar panels are almost an afterthought. A means to an end.

For example, the M-Kopa 6500 is marketed as a product to grow businesses through reliable refrigeration; its tagline reads:

Grow your business with an M-KOPA solar fridge that lasts all day. Serve chilled drinks and food to keep your customers happy. Save time and money by keeping food fresh longer

The second piece of innovation is in payments. Micropayments and mobile-first pay as you go schemes are booming in Africa. Topping up your energy account may seem unheard of in the West but is a growing practice in the region. Rather than buy solar panels up front, one can pay through a mobile app only for the energy the appliances consume.

Prefer to own the panels instead but don’t have a borrowing history? M-Kopa will sort that out for you too, along with a credit history for your next purchase.

The energy providers of the continent’s future appear foreign to the Western eye. They bundle together energy generation with consumer goods and asset financing schemes in response to their customers’ needs. Despite these challenges, they have the unique opportunity to build on a blank canvas, unencumbered by last century’s infrastructure.

Sub-Saharan Africa is an interesting case study in both the shortcomings of the grid and the possibilities of an unbundled energy supply. The rest of the world should watch closely as the future of energy emerges from the problems of our past.

If you enjoyed this issue, could you do me a favour and hit the like button below?

👇