Moby Dick marked an unlikely entry in my final year reading list for a course on climate science. The story of a man trying to catch his white whale is set against the backdrop of a free market that was incentivising the extinction of a species. For a time, whale fat illuminated the Western world and as the population of whales plummeted, the price skyrocketed. Whalers became ever more daring, spending weeks on ship in search of a single catch that could make their fortunes. This in turn reduced the population further, which pushed the price further and perpetuated the vicious circle.

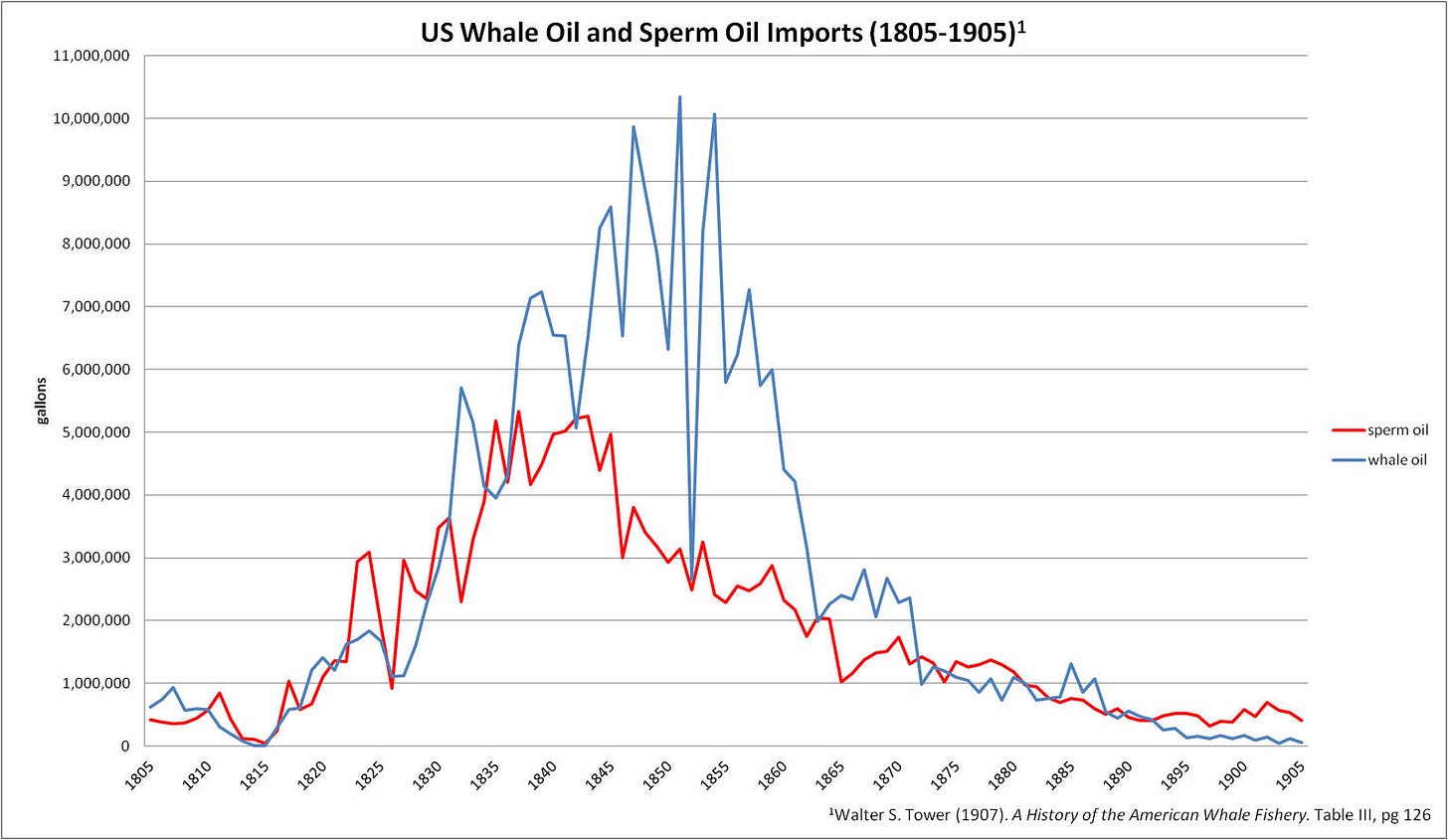

The exponential rise and subsequent fall in whale oil consumption in the 19th century

This case study can be twisted to serve both environmentalists and free-market proponents alike. Free market signals didn't curtail consumption but accelerated the exponential growth till the whale population collapsed — short term profits were incentivised over sustainable whaling. On the other hand, society never saw the prophesied, apocalyptical blackouts as alternates were found and supplanted the need for whale oil. Production techniques for kerosene continued to improve, in parallel, and quickly made whale oil almost redundant. Although the population of free whales may never recover, lights around the world barely flickered as innovation kept humanity on its course.

I have found this story to be a powerful reminder of not only the limits of free-market economics but also its ingenuity. This double-edged sword remains highly relevant to today's problems. It can broadly apply to any area where the economy incentivises short-term profits while ignoring externalities and their associated effects. Early whalers believed the oceans to be an infinite reservoir just as industrialists looked to the bottom of oil wells or the sky for it's never-ending capacity to absorb and dissipate. However, the key distinction between our overproduction of greenhouse gases today and the overconsumption of wales is that the former poses a far greater existential risk than a few empty candle sticks ever did.

To hack the planet, we need to hack the economy

As in the 19th century, the structure of our economy handcuffs any major effort to fight climate change. The need for growth means our consumption increases and competition means that fossil fuels power this consumption. In many ways, there is still a painful need to increase our production of greenhouse gases in much of the third world as increasing the energy usage per capita is one of the best mechanisms we have to lift the poor out of poverty.

The two main ways government's have approached the issue of coupling environmental externalities and free market economics is through tax and emissions trading systems. The former is relatively straight forward but receives a lot of political pressure, often cited as a growth tax. The latter normally falls under 'cap and trade' mechanisms where emission allowances are handed out and the market determines the price at which extra capacity can be bought or surplus can be sold off.

Climate change was a problem in search of a solution, emissions trading was a solution in search of a problem, and international negotiations served as the forum in where this problem and this solution eventually came to be united.

Existing schemes have often come under heavy criticism. These markets have been plagued by either low trading prices, representing an overabundance of carbon credits, or high volatility that creates uncertainty for any business trying to create a coherent renewables strategy. Even excluding the collapse in value of credits in 2007, the average price has been far lower than the estimated average cost (~$40 - $60) of averting one metric ton of carbon. Despite almost half of EU's emissions being covered by such schemes, less than a fifth of the worlds production has any form of penalty. This means that we're charging a small fee on a small fraction of all emissions. Clearly not the strategy we need to slash annual pollution by half.

European ETS prices (2009 - present) — the price has remained below $10 for much of its history despite the real cost to businesses of reducing carbon emissions being far higher

Outside of just trading, the European Emissions Trading Schemes attempts to incentivise green investment through the Clean Development Mechanism. Companies offset their emissions through investing in renewable energy projects in developing countries. This has come with a whole host of other problems. For example, it remains unclear whether there has been any additional marginal value from such investments or whether much of these projects would have secured funding anyways. Furthermore, the benefits of these projects, once completed, are not as green as one would hope, with investors leaning towards big investments like hydroelectric dams over opting for the most renewable ones.

If economists ruled the world, carbon prices would drive most of the action on climate change - Economist May 23rd, 2020

Unfortunately, economists do not rule the world. However, software has played a big role in the last 20 years to forge efficient marketplaces across a variety of industries and has an opportunity to again do so. Just as Google facilitates advertising - through dynamic pricing, precise targeting, building trust between buyers / sellers - we should look at similar mechanisms to fortify emissions trading. For these systems to truly work, we need to create accountability in the tooling, reduce the transaction costs of trading and capture data on the real impact.

For example, Pachama, a startup based in silicon valley, is trying to build trust in carbon capture markets through technology. They use satellite imagery to determine the level of forestation and thus the amount of carbon recaptured by any given project. Then, the corporate social responsibility arms of companies can buy into machine-validated green programmes, conveying real meaning to their acquired carbon credits.

Another exciting area will be platforms that facilitate distribution of renewable energy. This paper argues that platforms are necessary in connecting decentralised resources (e.g., Airbnb connects people to apartments across the world) and that this will broker the next phase of energy transition. Rather than sticking with your default energy provider, you may one day be able to select the windmill in the country-side or your neighbour's solar panel as your source of the energy for any given day. Thus, platforms empower consumers (everyday people or businesses) to make decisions on their environmental impact rather than hide behind a veil of ignorance.

The effect would be to shift away from treating electricity as a commodity. Such transparency would mean that green energy would be worth more per joule than its counterpart. I certainly would pay more for green, local energy and I suspect businesses with strong CSR targets would do the same. Higher prices would incentivise greater supply and the free market wheel would start to roll in the right direction. Finally, those that are less able or less inclined to afford better sources of energy can continue to use fossil fuel until the supply catches up to demand and prices even out — forced by Adam Smith’s invisible hand to make the right decision.

Unfortunately, neither of the two approaches yet promise the desired scale. We will likely need a tightly coupled mix of bigger policy, better economics and more innovative technology to hack our way to a green economy.

Perhaps one of the best US based carbon markets is RGGI - and you can use https://www.kotoo.earth to help inflate it's price as a consumer!